威廉·M·阿尔金(William M. Arkin,马里兰大学理学学士)是一位独立作家和顾问。他曾担任国际研究小组(即所谓的哈佛研究小组)的军事顾问,并于1991年至1993年在战后的伊拉克呆了七周,视察了350多个被轰炸的地点,采访了伊拉克官员、士兵、技术人员和平民。他广泛地讲述他对战后伊拉克的观察。1995年,他获得了约翰·D和凯瑟琳·T·麦克阿瑟基金会的资助,研究战争中电力系统的轰炸问题,并于1996年作为人权观察的顾问访问了黎巴嫩,视察了以色列的袭击事件。他目前正在撰写一本关于空战真实影响的书—— 《瞄准伊拉克》。阿尔金1974年至1978年担任陆军情报分析员,著有或合著了九本军事书籍,包括著名的《核武器数据手册》系列。他的最新著作是《美国军方在线:国防部互联网访问指南》。他是《原子科学家公报》的专栏作家。

-

Rick Atkinson, Crusade (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1993), 288-89.

-

Colin Powell with Joseph E. Persico, My American Journey (New York: Random House, 1995), 513.

-

Of more than 215,000 individual weapons dropped, 10,500 were laser guided. Of these, fewer than 8,000 were used against “strategic targets.” See Thomas A. Keaney and Eliot A. Cohen, Gulf War Air Power Survey (hereafter GWAPS), vol. 5, pt. 1, 549-54.

-

A total of 84,200 tons were dropped by US aircraft. Department of the Air Force, Reaching Globally, Reaching Powerfully: The United States Air Force in the Gulf War: A Report (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Air Force, September 1991), 28; Department of Defense, Conduct of the Persian Gulf War: Final Report to Congress, vol. 2 (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 1992), T–78.

-

The Ba’ath party headquarters took 28 bombs, Iraqi air force headquarters took 17, and Muthenna airfield took 25. Information taken from an informal F–117 strategic target list and “scorecard,” 37th Fighter Wing, obtained by the author. Six Tomahawks were also fired against Ba’ath party headquarters on 17 January. GWAPS, vol. 4, pt. 1, 173; and vol. 2, pt. 1, 124, 246.

-

See for example John A. Warden III, “Employing Air Power in the Twenty–first Century,” in The Future of Air Power in the Aftermath of the Gulf War, ed. Richard H. Schultz Jr., and Robert L. Pfaltzgraff Jr. (Maxwell AFB, Ala.: Air University Press, 1992), 81; John R. Pardo Jr., “Parallel Warfare: Its Nature and Application,” in Challenge and Response: Anticipating US Military Security Concerns, ed. Karl Magyar et al. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1994), 283; Casey Anderson, “`Hyperwar’ success may alter AF doctrine,” Air Force Times, 22 April 1991, 24; idem, “Air Force looks at going deep quickly in future wars,” Navy Times, 29 April 1991, 27; “Catching up with doctrine,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, 29 June 1991, 1174.

-

Quoted in Samir al–Khahl, “Iraq and Its Future,” New York Review of Books, 11 April 1991, 10.

-

Private written communications with the author.

-

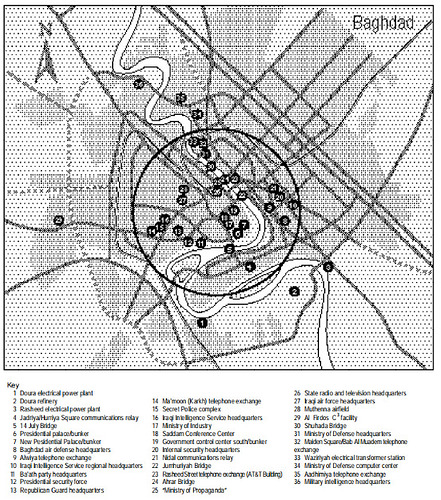

This excludes Rasheed airfield and targets in the suburbs of Abu Ghraib and Taji.

-

“We did not carpet bomb downtown Baghdad,” said Gen Merrill McPeak, Air Force chief of staff, in his end of the war briefing. “It’s obvious to anyone who has been watching on television, the pictures of Baghdad neighborhoods untouched, people driving around, walking around on the sidewalks and so forth . . .” (emphasis added). Gen “Tony” McPeak, USAF, DOD news briefing, Friday, 15 March 1991, 2 P.M. EST. “To do the things that we did in Baghdad in the old days would have taken large numbers of bombs with a lot of damage to surrounding areas,” added Lt Gen Charles Horner. “These guys went out there night after night and took out individual buildings” (emphasis added). Eric Schmitt with Michael R. Gordon, “Unforeseen Problems in Air War Forced Allies to Improvise Tactics,” New York Times, 10 March 1991, A1.

-

Paul Lewis, “Iraq’s Scars of War: Scarce and Precise,” New York Times, 22 April 1991, A1.

-

Milton Viorst, “Report from Baghdad,” The New Yorker, 24 June 1991, 58.

-

Erika Munk, “The New Face of Techno–War,” The Nation, 6 May 1991, 583.

-

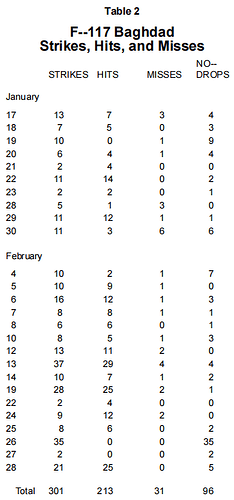

There were actually 2,592 potential opportunities to drop bombs, but many strikes were aborted. See Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, vol. 2, T–75; USAF Fact Sheet, “37th Fighter Wing, Operation Desert Shield/Operation Desert Storm,” current as of November 1991. A strike is to be distinguished from a sortie by the fact that most F–117 sorties included two distinct strikes with one weapon earmarked to be dropped on one aimpoint and a second bomb earmarked to be dropped on a second aimpoint. Occasionally, the aimpoints were at the same target, but far more often, they were at different ones, sometimes at great distances apart. Information on ordnance expenditures was provided by CENTAF in response to a Freedom of Information Act request: 1,316 GBU–10, 33 GBU–12, 718 GBU–27, and four Mk84LD. The slightly different 2,077 figure is contained in letter, 37th Fighter Wing (37 OSS) to the author, subject: Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Request #92–01, 11 February 1992.

-

Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, vol. 2, T–75.

-

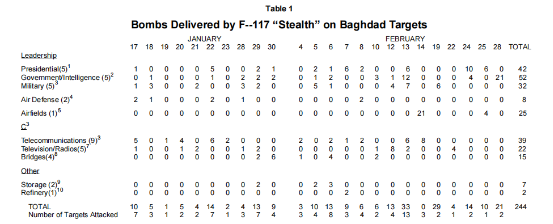

Informal F–117 strategic target list and “scorecard,” 37th Fighter Wing. These aircraft dropped 244 bombs (11 percent of stealth’s total). A total of 96 Baghdad sorties were aborted and weapons were not dropped due to weather, air defenses, the inability of the pilots to acquire the target, or equipment malfunctions (see table 2).

-

Ibid.

-

The ten top stealth targets include the Samarra chemical weapons plant (149 missions), Salman Pak biological and chemical weapons development facility (72 missions), Ubaydah bin Al Jarrah airfield in Kut (72 missions), Balad airfield (60 missions), Tallil airfield (57 missions), Tuwaitha nuclear research center (56 missions), Ba’ath party headquarters (55 missions), Al Asad airfield (48 missions), H2 airfield (47 missions), and Qayyarah airfield (39 missions).

-

Perhaps the White House’s pressure on news media executives to remove their reporters from Baghdad prior to the bombing had other purposes, but the news media understood Marlin Fitzwater’s personal entreaties as a warning that people in Baghdad were “in grave danger” given the intensity of bombing that would occur. Peter Arnett, Live from the Battlefield (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 363–64. See also John R. MacArthur, Second Front: Censorship and Propaganda in the Gulf War (New York: Hill and Wang, 1992), 185-87.

-

Gen H. Norman Schwarzkopf and Lt Gen Charles A. Horner, CENTCOM news briefing, Riyadh, Friday, January 18, 1991, 7 P.M. EST.

-

Air Force Posture 1995, Joint Statement of Secretary of the Air Force Sheila E. Widnall and Chief of Staff General Ronald R. Fogleman: Testimony before the House National Security Committee, 22 February 1995, 18; Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, 156, 222. See also Lt Gen Charles A. Horner, Stealth and Desert Storm, Testimony before the House Defense Appropriations Committee, 30 April 1991, 2; “The Value of Stealth,” Testimony by General John M. Loh before the House Defense Appropriations Subcommittee, 30 April 1991, 3.

-

By the end of the first week, a total of 51 stealth and 36 Tomahawk missile strikes, supplemented by eight F–16s and four F–111Fs, were scored as having been flown against leadership targets. GWAPS, vol. 5, pt. 1, 419–25. F–16 sorties were flown against 3d Corps headquarters in Kuwait, formally part of the leadership category. Four F–111Fs were tasked to hit Saddam’s “Tikrit summer house” on the first night, and one strike was reported as successful. F–111F target list and “scorecard” obtained by the author.

-

On 30 January, Jordan’s Foreign Ministry said that four of its nationals and one Egyptian were killed in deliberate and brutal allied air attacks on the Baghdad–Amman highway. BBC World Service, Gulf Crisis Chronology (London: Longman Current Affairs, 1991), 209. See also UPI (United Nations), “UN Leader Condemns Reported Bombing of Jordanian Drivers by Allied Forces,” 4 February 1991; Rick Atkinson and Dan Balz, “US: Iraq Exploiting Civilians,” Washington Post, 5 February 1991, A1. The President of Tunisia, Zini El Abadine Ben Ali, told the UN on 30 January that the destruction of Iraq was “intolerable.”

-

James A. Baker III with Thomas M. DeFrank, The Politics of Diplomacy (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1995), 402, 404.

-

The president’s address before a joint session of Congress on the State of the Union, 29 January 1991, contained in Foreign Policy Bulletin, January-April 1991, 58.

-

Michael R. Gordon and Bernard E. Trainor, The Generals’ War: The Inside Story of the Conflict in the Gulf (Boston: Little, Brown, 1991), 312-13. Gordon and Trainor state that about a hundred strikes had occurred in Baghdad by the two–week mark, but they overestimate (see table 1).

-

Mark Fineman, “Smoke Blots Out Sun in Bomb–blasted Basra,” Los Angeles Times, 5 February 1991, 7; Nora Boustany, “Iraq Waits `Impatiently’ for Ground War to Start,” Washington Post, 8 February 1991, A16; Carol Rosenberg, “Scenes of war’s havoc,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 10 February 1991, 1A. Brig Gen Richard Neal responded to the claims with a lengthy explanation that substantiated hidden damage: “It’s important to understand that Basra is a military town in the true sense. . . . As a result of all of these different targets that are close to radio transmission stations, communications places, POL [petroleum, oil, and lubricants] storage, chemical plants, significant warehousing capabilities . . . it’s very difficult for us to separate these. But even having said that, I think our targeters and the guys that deliver the ordnance have taken extraordinary steps to try and limit collateral damage. But I will be quite frank and honest with you, that there is going to be collateral damage because of the proximity of these targets close to, abutting civilian sites.” (CENTCOM news briefing, 11 February 1991, 10 P.M. EST)

-

Lt Gen Thomas Kelly, DOD news briefing, 7 February 1991, 11:30 P.M. EST.

-

On 5 February, Foreign Minister Tariq Aziz said that 428 Iraqi civilians had been killed and 650 wounded in bombing attacks since the war began. On 6 February, the New York Times reported that 108 Iraqi civilians had been killed and 249 wounded in attacks on residential neighborhoods. Alan Cowell, “Iraq Suspending Fuel Sales, As Raid Widens Shortages,” New York Times, 6 February 1991, A11. On 8 February, some 600 civilian fatalities were quoted. Nora Boustany, “Iraq Waits `Impatiently’ For Ground War to Start,” Washington Post, 8 February 1991, A16. The Iraqi Minister of Religious Affairs claimed on 11 February that “thousands” of civilians had been killed or wounded in bombing, a significantly higher figure than the previous 650 dead and 750 wounded given out by the Information Ministry. “Iraqi Lifts Estimate of Civilian Loss to Thousands,” New York Times, 12 February 1991, A13. The statement was obviously intended for Arab audiences.

-

Rear Adm Mike McConnell, DOD news briefing, 22 February 1991, 3:30 P.M. EST.

-

Air Force/Checkmate briefing (TS/LIMDIS), “Instant Thunder: Proposed Strategic Air Campaign,” 14 August 1990, declassified and released under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

-

GWAPS, vol. 1, pt. 1, 109. Given Iraq’s highly centralized decision making, “isolation and incapacitation” was labeled a bombing objective of “overriding importance.” Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, 199. See also GWAPS, vol. 2, pt. 1, 22. “The intent was to fragment and disrupt Iraqi political and military leadership by attacking its C2 [command and control] of Iraqi military forces, internal security elements, and key nodes within the government. . . . The target set’s primary objective was incapacitating and isolating Iraq’s senior decision–making authorities,” the report went on to say. Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, 126-27.

-

GWAPS, vol. 1, pt. 1, 157.

-

Airpower in the Gulf, 45.

-

GWAPS, vol. 1, pt. 1, 10, 115; vol. 2, pt. 2, 280.

-

GWAPS, vol. 2, pt. 1, 206.

-

Air Force/Checkmate briefing, “Desert Storm,” n.d. (postwar circa 1992), released under the FOIA.

-

GWAPS, vol. 1, pt. 1, 164. At Warden’s briefing on 17 August, Schwarzkopf said that “by the end of the first week we’ll have all kinds of pressure to get out! The [United Nations] Security Council will scream. If we can be done in six days, we can say we’re sorry and get out. [It] may not be pretty, but we’re gonna get this.” Richard T. Reynolds, Heart of the Storm: The Genesis of the Air Campaign against Iraq (Maxwell AFB, Ala.: Air University Press, 1995), 109.

-

GWAPS, vol. 1, pt. 1, 165.

-

GWAPS, vol. 1, pt 1, 123; vol. 1, pt 2, 173.

-

GWAPS, vol. 2, pt. 2, 282.

-

These targets included the Rasheed street communications center (the so–called AT&T Building), Baghdad international RADCOM transmitter, Jenoub (Ma’moon) communications facility, Baghdad international receiver/radio relay station (north of Al Firdos), Baghdad military intelligence headquarters, Baghdad RADREL terminal air defense headquarters (Wahda), Ba’ath party headquarters, Doura electrical power plant, Iraqi air force headquarters, Baghdad TV center, Iraqi Intelligence Service headquarters, Maiden Square telephone exchange (Bab al Muadem), Ministry of Defense headquarters, Ministry of Information/Culture, the MOD/National Computer Center, New Presidential Palace, the Baghdad presidential residence and bunker, and the Shemal telecommunications exchange.

-

These included Baghdad internal security headquarters, Baghdad military intelligence headquarters, Ba’ath party headquarters, Iraqi air force headquarters, Iraqi Intelligence Service headquarters, Ministry of Defense headquarters, Ministry of Information/Culture, the MOD/National Computer Center, New Presidential Palace, and the presidential bunker.

-

GWAPS, vol. 1, pt. 1, 90; vol. 2, pt. 2, 78; Gordon and Trainor, 365.

-

GWAPS, vol. 1, pt. 1, 89.

-

Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, 133.

-

GWAPS, vol. 2, pt. 2, 285-87; Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, 238; Atkinson, 295.

-

The announcement by Iraq was made on 6 February. “Iraqis Sever Ties with Six Nations,” New York Times, 7 February 1991, A1; Nora Boustany, “Iraq Charges High Civilian Toll in Air Raids,” Washington Post, 7 February 1991, A1; Alfonso Rojas, “A bridge too near for civilians as bombers strike,” Guardian (London), 8 February 1991.

-

On 30 January, an attack against the downtown Ahrar bridge, near the Mansour Melia Hotel, mistakenly hit the Central Bank in the old market area; there were no casualties. Baghdad bridge attacks were reported in R.W. Apple Jr., “Heaviest Shelling by the Allies Yet Rips South Kuwait,” New York Times, 13 February 1991, 1; “Two Government Departments Hit in Allied Air Strikes on Baghdad,” New York Times, 13 February 1991, A14; “Iraqi Lifts Estimate of Civilian Loss to Thousands,” New York Times, 12 February 1991, A13. During a visit to the Marines, Schwarzkopf was asked about the bombing of the Baghdad bridges on 13 February. He stated that there was “a very, very, very good reason for bombing that bridge in Baghdad,” which he wrongly said was part of a key supply route that was being used to support Iraqi troops in Kuwait. UPI (Northern Saudi Arabia), “Schwarzkopf Defends US Bombings,” 14 February 1991. The bombing of the Central Bank was first reported in Lee Hockstader, “Battered Baghdad Struggles On: Citizens of Iraqi Capital Bemoan Reversal of Fortunes,” Washington Post, 28 February 1991, A1.

-

The GWAPS speculated that television’s publicizing of the Nasiriyah bridge strike on 4 February may have influenced Powell. “Civilian deaths at that site may have increased Powell’s reaction to F–117 night strikes against bridges in downtown Baghdad.” GWAPS, vol. 2, pt. 1, 221. “Decision makers in Washington appear to have concluded that these effects [from severing the bridges] were not worth the adverse media publicity that a systematic attack on Baghdad’s bridges would, in all likelihood, have produced. . . . GWAPS could find no unequivocal documentary record of bombing restrictions emanating from Washington.” GWAPS, vol. 2, pt. 2, 287. See also Eric Schmitt, “Iraq Said to Hide Key War Center in a Baghdad Hotel For Foreigners,” New York Times, 14 February 1991, A1; and R.W. Apple Jr., “Allies to Review Air Target Plans to Avoid Civilians,” New York Times, 15 February 1991, A1.

-

Department of the Army, Operation Desert Shield/Storm, MI [Military Intelligence] History, vol. 2, n.d. (1991), 8–113, partially declassified and released under the FOIA. On 6 February, CENTCOM reported that “Iraqi leadership appears to remain in control of its military forces.” CENTCOM SITREP for 6 February 1991, released under the FOIA.

-

GWAPS Summary Report, 70. Since communications were reestablished, the targets “required persistent restrikes.” Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, 127. National–level capability could be repaired, “and thus needed to be attacked repeatedly.” Ibid., 201.

-

In the words of the Gulf War Air Power Survey, “To all intents and purposes the civilian losses ended the strategic air campaign against targets in Baghdad.” GWAPS, vol. 2, pt. 1, 206. See also Gordon and Trainor, 326-27.

-

See for example Rick Atkinson and Dan Balz, “Bomb Strike Kills Scores of Civilians in Building Called Military Bunker by U.S., Shelter by Iraq,” Washington Post, 14 February 1991, A1; R. Jeffrey Smith, “Building Was Targeted Months Ago as Shelter for Leaders,” Washington Post, 14 February 1991, A25; Michael R. Gordon, “U.S. Calls Target a Command Center,” New York Times, 14 February 1991, A17.

-

Lt Gen Thomas Kelly, USA, and Capt David Herrington, USN, DOD news briefing, Wednesday, 13 February 1991, 3:30 P.M. EST.

-

Arnett, 399-400.

-

Literaturnaya Gazeta, 27 February 1991, quoted in GWAPS, vol. 1, pt. 1, 68.

-

Targets identified by the US in this area included the Baghdad Conference Center, the Rasheed Hotel, the Ministry of Industry, Government Control Center South (a communications/command center northwest of the New Presidential Palace), the New Presidential Palace and command center, a presidential residence and command center, Ba’ath party headquarters, Republican Guards headquarters, and the Presidential Security Service compound.

-

Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, 95.

-

Atkinson, 274. By the end of the second week, the Air Force wrote, “With even back–up communications systems disrupted, Saddam Hussein was reduced to sending orders from Baghdad to Kuwait by messenger; the trip took at least 48 hours” (emphasis added). Reaching Globally, Reaching Powerfully: The United States Air Force in the Gulf War, 23. Schwarzkopf also stated that “Saddam Hussein and the Iraqis have been forced to switch to backup systems, and those systems are far less effective and more easily targeted.” Gen Norman Schwarzkopf, Brig Gen Buster Glosson, CENTCOM news briefing, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 30 January 1991. “The bombing campaign seriously degraded Iraq’s national communications network by destroying Saddam Hussein’s preferred secure system for communicating with his fielded forces.” Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, 200.

-

GWAPS, vol. 1, pt. 1, 69. Iraqi deserters in Desert Storm indicated high reliance on couriers. Interrogations of captured sailors after the Battle of Bubiyan revealed that secret orders were hand delivered from Iraqi naval headquarters in Basra to the captains of the Polnocnyy LSMs ordering them to sail their ships to the Bandar Khomeini port in Iran. CNA, Desert Storm Reconstruction Report, vol. 6, 4-7, partially declassified and released under the FOIA.

-

Destruction of central C3, Glosson thought, would “put every household in an autonomous mode and make them feel they were isolated. I didn’t want them to listen to radio stations and know what was happening. I wanted to play with their psyche.” GWAPS, vol. 1, pt. 1, 93.

-

Though a large dose of “strategic psychological operations” was meant to influence the people of Baghdad, for a variety of reasons, the PSYOP campaign was never implemented.

-

A UN postwar survey stated that at least 400,000 telephone lines “were damaged beyond repair” that “the main microwave links connecting most of the cities were also damaged,” with additional C3 targets damaged to various degrees. International and regional communications, consisting of the two satellite earth stations at Dujail and Latifiyah, two international exchanges in Baghdad, and microwave and coaxial cable links to Turkey, Syria, Jordan, and Kuwait, were destroyed. Sadruddin Aga Kahn Report, 15 July 1991, 3, 7, annex 10. Also based upon the author’s observations in Iraq in August-September 1991 and February 1993.

-

John A. Warden III, “Employing Air Power in the Twenty–first Century,” in Schultz and Pfalzgraff, 65.

-

Even postwar analysis seems to accept without question that the bombing was having a psychological impact in Baghdad. “Undoubtedly,” one postwar report states, “the impact of six Tomahawks hitting the Iraqi Ministry of Defense between 1010 and 1017 [on 17 January] did little to improve morale of those in the building or neighborhood.” GWAPS, vol. 2, pt. 1, 143. “The destruction of several of the Iraqi government’s larger buildings in Baghdad would obviously have had psychological effects on both government and people” (167).

-

A League of Airmen, 130.

-

Defense Intelligence Agency, “Iraqi Short–Range Ballistic Missiles in the Persian Gulf War: Lessons and Prospects,” defense intelligence memorandum, March 1991, obtained by the author, and also quoted in Gordon and Trainor, 498. The General Accounting Office also falls into the trap of crediting physical destruction with functional effect, stating in a report on the performance of the Tomahawk missile that its use during daytime “had the added benefit of maintaining psychological pressure on the Iraqis in and around Baghdad.” US General Accounting Office, “Cruise Missiles: Proven Capability Should Affect Aircraft and Force Structure Requirements,” NSIAD–95–116, April 1995, 25. Tomahawk was only an occasional visitor in the sparse campaign and psychological pressure was merely the alleged impact.

-

Author’s observations in Iraq in August-September 1991 and February 1993, and interview with Ministry of Oil, Telecommunications, and Defense officials. UNSCOM concluded that “virtually the entire computer capacity” at Tuwaitha, as well as elements like electromagnetic isotope separation components and nuclear materials, had been removed before the war began. The materials had been moved to “emergency storage” in pits located in a farmland area a few miles from the nuclear facility. GWAPS, vol. 2, pt. 2, 365-66. UN inspection teams discovered that “most production equipment, components, and documents had been removed before the beginning of the air campaign.” Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, 208. See also US Congress, House Foreign Affairs Committee, Iraq Rebuilds Its Military Industries, staff report, 29 June 1993, 9; and John Simpson, From the House of War (London: Arrow Books, 1991), 159.

-

John Warden wrote as much after the war, stating that “first–day attacks did considerable damage to headquarters buildings (and presumably to files, computers, and communications)” (emphasis added), never with a hint of irony. John A. Warden III, “Employing Air Power in the Twenty–first Century,” in The Future of Air Power in the Aftermath of the Gulf War, 70.

-

Reaching Globally, Reaching Powerfully: The United States Air Force in the Gulf War, 21. Lockheed, in its promotional brochure about stealth, states that “pilots were informed in advance of certain key rooms within these buildings that should be hit, and the videotape records demonstrate that they did so with astonishing precision.” “Stealth: Our Role in the Gulf,” Lockheed Horizons 3, no. 1 (June 1991): 5. See also “War’s New Science,” Newsweek, 18 February 1991, 38; Philip Caputo, “War Torn,” New York Times Magazine, 24 February 1991, 34; Michael A. Dornheim, “F–117A Pilots Conduct Precision Bombing in High Threat Environment,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, 22 April 1991, 51; and Triumph Without Victory: The Unreported History of the Persian Gulf Conflict (New York: Times Books, 1992), 217.